A labour of love

For over 40 years, Paul has lived, breathed, and nurtured the NT building in various roles including production lighting, and repertoire planning. He was Co-Director for Major Projects during the NT Future building refurbishment, and took on his current role in 2017.

The role of Head of Building Design was inherited from his work on NT Future – a long-term, £83 million project, which ran for several years whilst the building remained open. His role then was to provide an interface between the architects and the stakeholders around the building. He learnt a lot about the building in that time, and there was a large element of sustainability as part of the project as well.

As Head of Building Design, Paul acts as a consultee, whenever someone wants to make changes – either temporary or permanent – around the protected building. A conservation management plan acts as the guide, and Paul’s the go-to person to talk to. Any changes need to go through a process with planning authorities and consultees. On the environmental side, his work involves changing the culture of the building, putting sustainability at the heart of it.

The challenges of listed status

Listed and historic buildings – like the NT – present a special kind of challenge to people who design signs. There’s a heady-mix of panic and passion when we consider the impact and importance of signs in these spaces, and the needs of people navigating them.

The NT was originally listed ahead of its first round of refurbishment, which was much-needed after years of opening six days a week. It was listed under the encouragement of its architect, Denys Lasdun, to prevent too many changes, and save the integrity of the design.

These days, planners are much more open to changes in listed buildings. They’re seen as living, functioning buildings that have to be able to grow and adapt to the changing world. Part of the challenge is that the NT is a creative organisation, full of creative people who want to leave their mark, and change things. But the concrete is not so forgiving!

The NT has a good relationship with the planners, and they understand where they can flex on things and understand what’s possible and allowed.

The architectural flavour of the NT

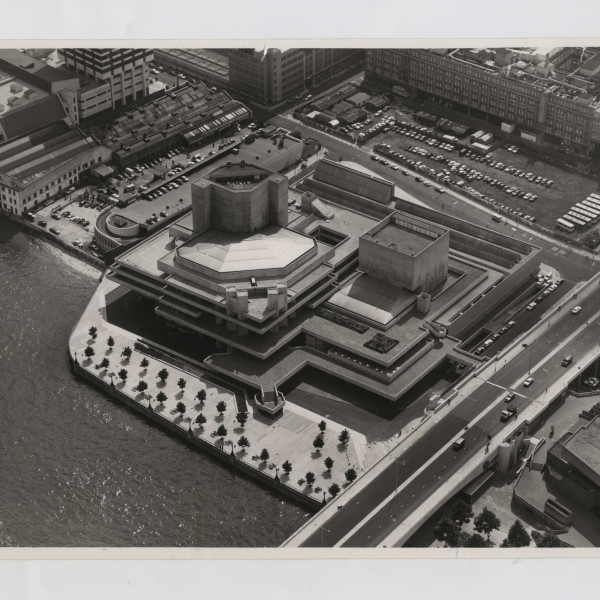

Originally conceived as two buildings – an opera house and a theatre – the NT was initially proposed to sit in front of the Shell building beside County Hall. As the design evolved, the opera house fell away – partly due to lack of interest and funding. So the design – containing two symmetrical structures – was essentially cut in half and moved to the current site.

That halved structure was then reworked to connect with Waterloo Bridge. However, elements retained from the first design give the architecture a distinct look and feel in some places. The building was made by pouring concrete into moulds made from planks of wood. Many people don’t realise that it’s very much a hand-built structure, and its concrete retains some of the characteristics of the wooden planks.

Opening at a time when concrete buildings from the 1960s were falling out of favour, the building and its architect met with some criticism. Delays due to strikes, industrial disputes, and a shortage of materials caused the construction work to drag on. It was one of those buildings in London that never seemed to be finished. It was also sat in isolation on one side of Waterloo Bridge.

At the time of construction, its simplicity, warmth, and detail were overlooked. Lasdun used a limited palette of materials, so it’s a very subtle design. His wife designed some aspects of the interiors, including the carpet, which now forms part of the listing and cannot be changed. The idea was to create a geological structure – like a rock face or cave – you go into the cave to see the magic of theatre, or as Lasdun called it ‘the word’.

A building that divides opinion

The NT was once listed as one of the most loved and most-hated buildings in the UK, at the same time. Although some people will never love concrete, they do love the cavernous interior spaces.

In the 1990s, when the building was re-lit with coloured lighting at night, people began to pay it more attention. At the same time, other changes – such as the removal of the road – helped to integrate the building more closely with the rest of the South Bank, and the subsequent changes that took place around the new millennium, including the Tate Modern and the Millennium Wheel (now the London Eye). Today, around 14 million people per year walk the South Bank. It’s one of the top ten things to do when visiting London.

Wayfinding fit for modern purpose

The NT building is used by different people in different ways. 1976 wasn’t that long ago, but since then, things have changed, creating challenges around modernising the building for contemporary audiences.

One of the main issues was wheelchair access. It just wasn’t thought about in the original design. It’s a complicated building – housing three separate theatres – which has lots of levels that are not connected by lifts. Making it accessible has been problematic.

The protected concrete finishes and the lack of logic around navigating the building is a wayfinding challenge that may never be completely resolved. Initially, it was designed to be porous – so you could come in at any level. Due to current public security issues, that’s now changed.

Inside, there’s a wonderful array of levels and vistas. This makes it unclear as to where anything is or how to get there! The original wayfinding was beautiful – polished metal signs with small arrows – but as a visitor, it often got you started and left the rest up to you.

On top of that, the foyers were designed to be theatrical and therefore atmospherically lit. That makes it difficult to see – like being at the back of the cave. The theatres and the toilets are well-hidden at the back. In the 1990s, this was addressed by colour-coding the signs and the tickets. The trouble was, no one noticed!

During NT Future, the wayfinding was simplified right down to the bare bones. Poster frames for each show were added to the stair signage because visitors are usually looking for the show and not the specific theatre. In addition, there’s now projection to guide visitors in the right direction to see their show. The toilets are not in a logical place, but the toilet signage is now more obviously lit. Visitors are also aided by greeters at the main entrance.

Balancing the building’s needs with revenue streams

With a bookshop and newly-refurbished restaurants, there’s a pressure to add signage to the building. Pop-up signs are never ideal, so how does Paul support those revenue streams with wayfinding whilst maintaining the integrity of the interior spaces?

Digital signage has been incorporated to enable internal stakeholders to promote their offer, with two large LED screens above the main entrance. There’s also talk of integrating digital signage behind glass entrance walls – but this is expensive and poses difficult questions to planners in terms of impact.

As signage does not often fall into the long-term planning, any proposal involves Paul’s approval and an informal conversation with the planning officer at Lambeth Council. Other consultees include the Twentieth Century Society, Historic England, and the Theatre’s Trust.

The greatest challenge is always the concrete itself. It seems very solid, but it’s actually quite delicate and vulnerable. It’s not very resilient. The board-marking texture isn’t very deep, so when cleaning it, there’s a danger that it can be worn down – particularly externally. It can’t be pressure washed, and the surface has weathered differently on different aspects of the building, so it’s difficult to colour-match repairs.

Culturally, what’s missing is the skill set to repair concrete buildings in the same way as stone or brick. The other problem is that there’s no precedent for knowing what damage protective coatings or other interventions might do to the concrete in 20 or 40 years’ time.

Heritage and sustainability

For Paul at the NT, it takes time and effort to ensure materials fit the heritage but are also sustainable. That means checking the embedded carbon of any products used. Lasdun’s limited materials – concrete, blue/black slate brickwork flooring, the carpet and stainless steel, black leather on the banquet seating, and Wenge wood – create a challenge.

Innovations are needed to balance heritage with sustainability. For example, since Wenge wood is now protected, the NT has to fake it by treating and manipulating oak to give a similar effect. There’s also the issue of longevity. Water-based finishes have a shorter lifespan than solvent-based products, which impacts the lifespan of certain items.

The NT building continues to evolve. Paul and his team are already planning future upgrades to ensure it can sustainably endure, and can continue to be enjoyed for generations to come. In Paul’s own words – it’s a happy building.

Watch this short video exploring Endpoint’s collaboration with the NT here.

Discover more about the history of the National Theatre. Visit their website www.nationaltheatre.org.uk

Our podcast is available on Spotify, Apple Podcast and YouTube. Don't forget to subscribe and rate us!